NASA is always keen to highlight the space agency’s many successes, and rightly so — those who pay for these expensive projects have a right to know what they’re getting for their money. And so the news was recently sprinkled with stories of the discovery of electron bursts beyond the edge of our solar system, caused by shock waves from coronal mass ejection (CME) from our Sun reflecting and accelerating electrons in interstellar plasmas. It’s a novel mechanism and an exciting discovery that changes a lot of assumptions about what happens out in the lonely space outside of the Sun’s influence.

The recent discovery is impressive in its own right, but it’s even more stunning when you dig into the details of how it was made: by the 43-year-old Voyager spacecraft, each now about 17 light-hours away from Earth, and each carrying an instrument so simple and efficient that they’re still working all after this time — and which very nearly were left out of the mission’s science payload.

Nice Work If You Can Get It

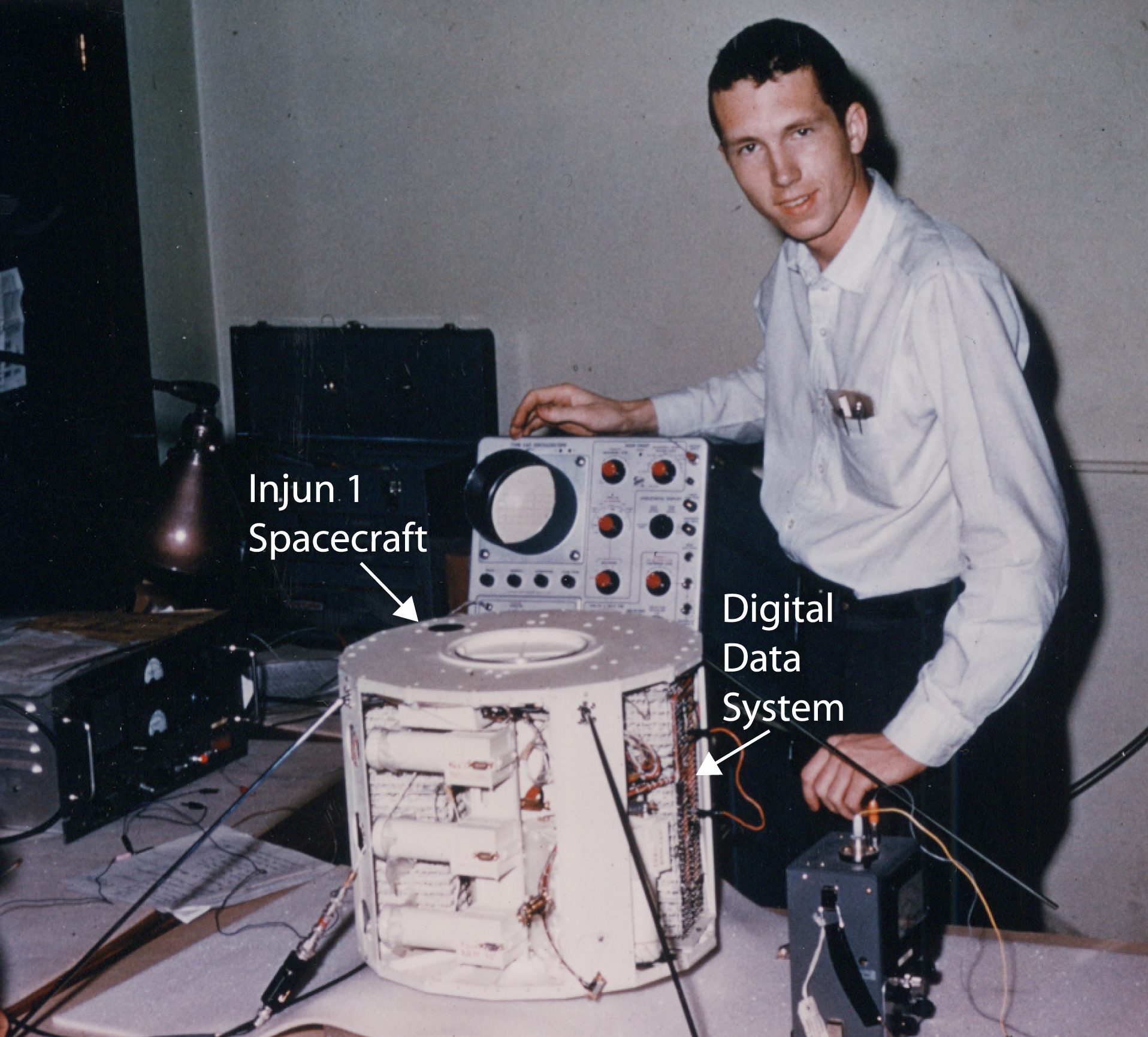

The instrument that made the discovery, the Plasma Wave Subsystem (PWS), can trace its lineage back at least as far as 1958. That’s when Donald Gurnett, an electrical engineering freshman at the University of Iowa, took a job in the lab of Dr. James Van Allen, who had recently discovered the radiation belts surrounding Earth that now bear his name. Van Allen and his team had used a special Geiger counter on Explorer 1, the first satellite flown by the United States, and the results were both exciting and foreboding. It was clear that Earth was surrounded by high-energy charged particles, which was a truly new discovery, but it also meant traveling in space may well be lethal. Moritz recently published a deeper dive into that topic.

More information was needed, so Van Allen set Gurnett to work on instruments for future satellites to explore the environment close to Earth. The team at the University of Iowa came up with innovative digital telemetry systems to replace the simple analog telemetry links used by Explorer 1 and other early satellites. They also devised a series of space radio and plasma wave experiments, in part to explore natural very-low-frequency (VLF) phenomena known as sferics, like whistlers and the “dawn chorus”. The experiments flew on satellite Injun-3 in 1962 and beamed back enough data for Gurnett to build his Ph.D. thesis on.

The lessons learned with these early experiments boosted the nascent field of space radio and plasma wave research and informed the construction of better instruments, which were flown on multiple missions through the 1960s and early 1970s. By then, NASA was deep in the planning stages for the Voyager missions, designed to take advantage of a rare alignment of orbits that would allow a probe to visit the previously unexplored outer reaches of the Solar System …read more

Source:: Hackaday